The evolutionary journey of modern cetaceans—whales, dolphins, and porpoises—is one of the most fascinating chapters in Earth’s history. These marine mammals trace their origins back to terrestrial ancestors, which gradually transitioned into fully aquatic creatures around 50 million years ago during the Eocene epoch. This remarkable adaptation highlights the dynamic nature of evolution.

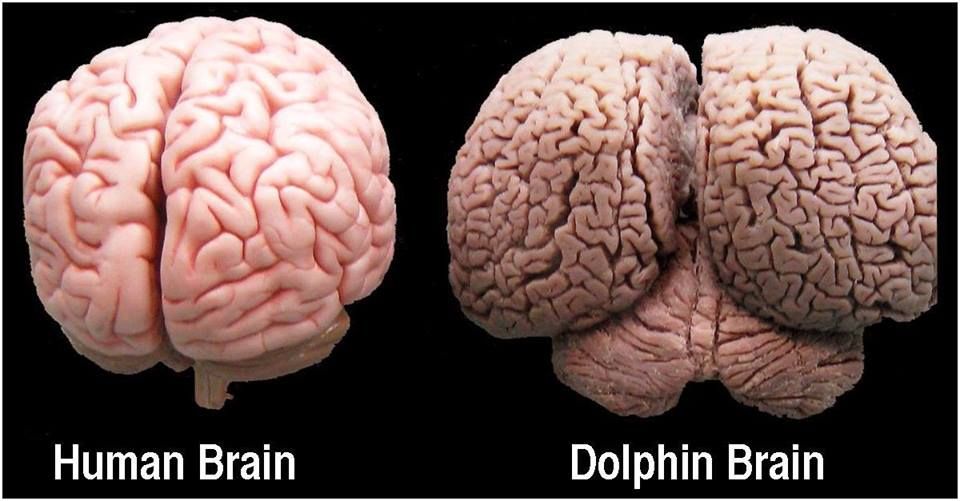

One of the most captivating features of modern cetaceans is their remarkable intelligence. For decades, researchers have explored the unique evolution of the cetacean brain, which exhibits distinct differences from other mammals, including humans. Cetaceans demonstrate extraordinary capabilities in communication, learning, empathy, and emotional depth.

While the human brain shares three primary segments with other mammals—the rhinic, limbic, and supralimbic regions, with the neocortex covering the supralimbic—the cetacean brain diverges in a striking way. Cetaceans possess a fourth cortical segment, representing a significant evolutionary leap.

This additional segment, known as the paralimbic lobe, creates a four-fold lamination in the cetacean brain, setting it apart from all other cranially advanced mammals, including humans. No other species has developed four distinct cortical lobes. The paralimbic lobe extends the sensory and motor functions of the human supralimbic lobe, underscoring the evolutionary complexity of cetacean cognition.

What does this mean exactly?

In humans, integrating sensory information from sight, sound, and touch requires signals to travel along lengthy neural pathways. This process results in a significant loss of both time and information, making our sensory integration slower and less efficient. In contrast, cetaceans, with their unique paralimbic lobe, are capable of processing sensory inputs far more rapidly, creating rich, integrated perceptions with a depth of information that we can hardly imagine.

While humans rely heavily on hand-eye coordination to manipulate our environment—building tools, constructing buildings, and creating vehicles—cetaceans exhibit intelligence in a completely different way. Their brain size, especially in large whales, suggests a high degree of cognitive complexity. For example, their sonar abilities far surpass human-made sonar technology, and sperm whales are even able to produce powerful sound blasts to stun prey, using the oil in their heads to amplify and project these sounds.

Cetaceans also have a distinct advantage in that their primary sense and method of communication are both auditory. While humans rely primarily on vision for perception and auditory language for communication, cetaceans have a more unified system. This means a dolphin, for example, can send an auditory image of a fish to another dolphin, effectively “projecting” the image in a way similar to how humans might use holographic technology to convey images.

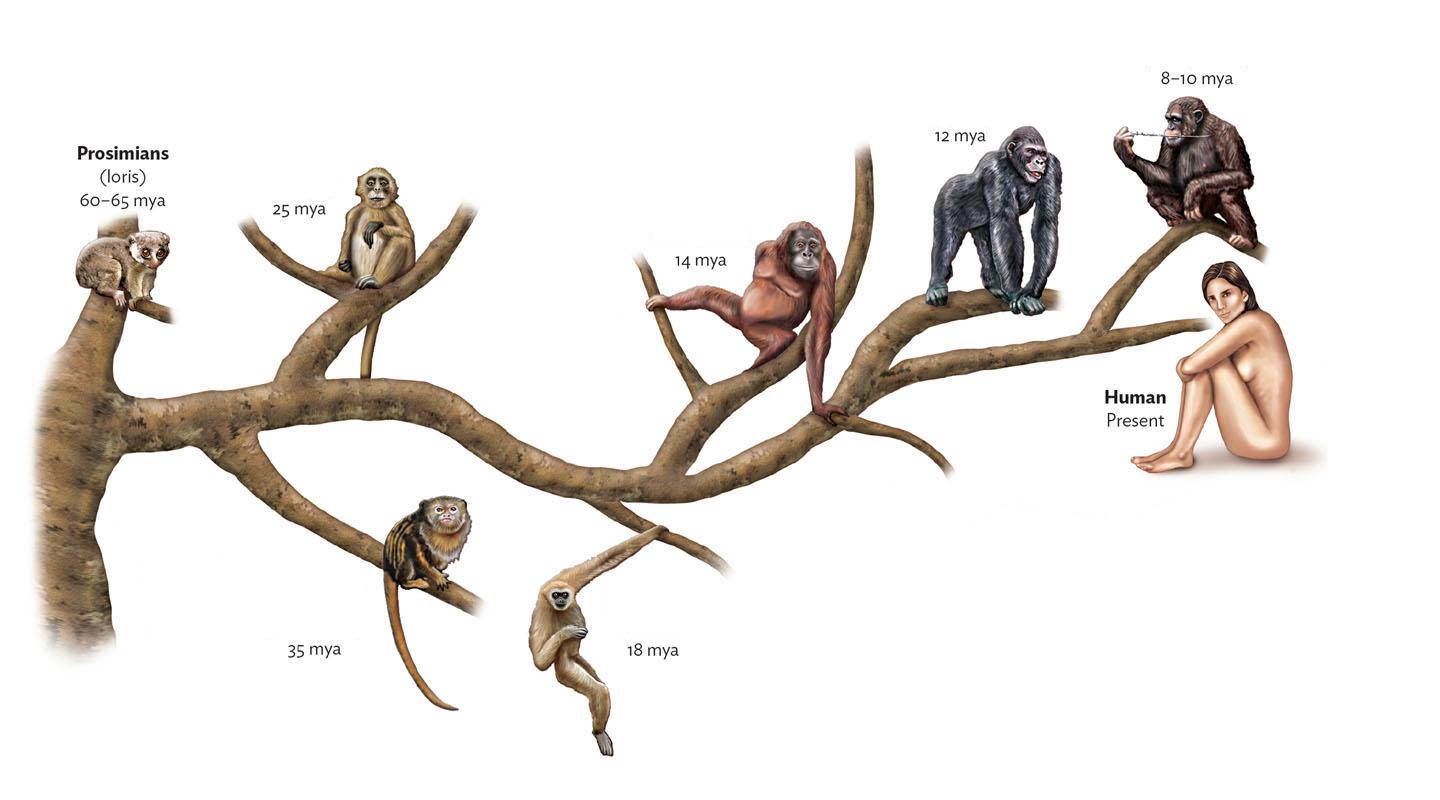

These advanced sensory and communication systems suggest that cetaceans possess a level of intelligence that is far more complex than most other mammals. This leads to the hypothesis that perhaps an ancient ancestor of modern primates might have followed a similar evolutionary path, returning to the sea and developing intellectual capabilities akin to those of cetaceans. Both cetacean and primate ancestors appeared around the same time period, raising the possibility of similar evolutionary developments in intelligence and cognitive function.

What if early primates living near coastal regions gradually evolved to become aquatic, much like the cetaceans? While this idea might lean towards “pseudoscience,” it’s worth considering a modern example of a people deeply connected to the water: the Sama-Bajau, also known as the “Sea Nomads.” This indigenous group, primarily found around the Tawi-Tawi islands in the Philippines, lives in stilt houses and boats, spending much of their lives on and in the water. Their unique way of life offers a glimpse into how humans might adapt to an aquatic environment over time.

They possess the remarkable ability to hold their breath for over three minutes and have been known to free dive to depths exceeding 230 feet. What’s extraordinary is how their physiology has adapted in such a relatively short period to accommodate their aquatic lifestyle.

One significant adaptation is their larger-than-average spleens, which aid in prolonged diving by storing and releasing oxygen-rich red blood cells. This trait has been identified as a genetic adaptation present among the Sama-Bajau regardless of individual diving frequency. Other genetic changes have been discovered that affect blood vessel constriction, oxygen flow to major organs, and CO₂ levels in the blood, enhancing their diving capabilities.

If such genetic adaptations can occur in just 1,000 years—a brief moment on the evolutionary timeline—imagine the changes that could transpire over 10,000 or even 100,000 years. This leads to a fascinating hypothesis: What if, millions of years ago, early primates living near coastal regions evolved similarly to the ancestors of modern cetaceans? Could their intellectual capabilities have advanced beyond those of their terrestrial relatives?

This speculative idea raises intriguing questions. Could reports of advanced technologies encountered in our oceans be evidence of an indigenous, advanced aquatic hominid species? Might such beings have evolved to utilize elements found in the ocean’s depths, achieving their own technological and societal advancements?

An intriguing addition to the discussion of advanced aquatic life is the octopus, a creature whose evolutionary path showcases remarkable intelligence and adaptability in a non-mammalian species. Octopuses are cephalopods known for their complex nervous systems and cognitive abilities that rival those of some mammals. Their brains are proportionally large for invertebrates, and they possess an intricate network of neurons not just in their central brain but also distributed throughout their eight arms. This allows for decentralized processing, enabling each arm to operate semi-independently—a feature that contributes to their extraordinary problem-solving skills.

Octopuses have demonstrated abilities such as tool use, navigation through mazes, and even escaping enclosures by observing and learning from their environment. Their capacity for mimicry and camouflage is unparalleled; they can change their skin color, pattern, and texture almost instantaneously to blend into their surroundings or communicate with other octopuses. This sophisticated level of control indicates advanced sensory processing and a high degree of environmental awareness.

The evolutionary advancements of the octopus highlight how intelligence and complex behaviors can evolve in completely different branches of the animal kingdom. Unlike mammals, whose intelligence is often linked to social structures and communication, octopuses are largely solitary creatures. Yet, they have developed cognitive abilities that suggest alternative evolutionary routes to high intelligence, driven by the demands of their environment and predatory lifestyle.

Connecting this to our earlier discussion, the octopus exemplifies how life in aquatic environments can lead to unique evolutionary outcomes, including advanced intelligence and specialized physiological traits. Just as cetaceans and the Sama-Bajau people have adapted remarkably to marine life, the octopus showcases a separate lineage where profound intelligence has emerged under the sea. This broadens the scope of our hypothesis: if such significant cognitive and physiological advancements can occur in cephalopods and marine mammals, it’s conceivable that other aquatic species—including hypothetical aquatic hominids—could evolve similarly advanced capabilities.

Moreover, considering the octopus’s ability to manipulate objects and its problem-solving skills, one might speculate on the potential for technology use in aquatic environments by intelligent species. While octopuses haven’t developed technology in the way humans understand it, their dexterity and intelligence suggest the possibility. If an aquatic hominid evolved with both high intelligence and the physical means to manipulate their environment, the development of technology—even advanced technology—could be within the realm of possibility.

In essence, the evolutionary advancements of the octopus serve as a testament to the diverse paths intelligence can take. They reinforce the idea that the oceans are a cradle for complex life forms with capabilities that can challenge our understanding of cognition and adaptation. This adds another layer to the hypothesis about advanced aquatic beings, suggesting that the evolution of intelligence in the sea is not only possible but has multiple precedents in Earth’s history.

Considering these diverse evolutionary advancements in Earth’s oceans—from the sophisticated intelligence of cetaceans and the adaptive physiology of the Sama-Bajau people to the complex cognition of octopuses—it prompts us to explore even more speculative realms. If our planet’s aquatic environments have given rise to such remarkable adaptations and intelligent life forms, could there exist indigenous species that have evolved beyond our current understanding? This line of thought leads us to the intriguing possibility of advanced aquatic beings native to Earth. Might the characteristics attributed to these beings be the result of an evolutionary path akin to that of the aquatic species we’ve discussed, suggesting that the depths of our oceans may harbor intelligent life forms that we have yet to discover?

Taking into account the descriptions of the common “little gray aliens”, could their light skin be a result of limited sunlight exposure in deep waters? Could their large, black eyes be adaptations for seeing in the ocean’s dark depths? Just as cetaceans have developed advanced auditory and sonar abilities, perhaps an aquatic hominid could have evolved to utilize broader ranges of the electromagnetic spectrum, potentially even developing telepathic abilities for communication.

While this remains in the realm of speculation, it highlights the incredible possibilities of evolution and adaptation, inviting us to explore the depths of our oceans—and our imaginations—for answers.

Leave a comment